In the heart of the 20th century, the American apparel industry stood as a pillar of domestic manufacturing strength, employing hundreds of thousands and fueling regional economies from the Carolinas to California.

However, as globalization surged and trade liberalization accelerated in the late 20th century, that same industry saw much of its production shift overseas.

Today, amid renewed political rhetoric, shifting consumer expectations, and recent trade tensions, the question looms: can the U.S. realistically bring apparel manufacturing back home?

The Historical Arc of Offshoring in the Apparel Sector

The mass exodus of apparel manufacturing from the United States began in earnest during the 1970s and 1980s, catalyzed by evolving trade agreements and cost-cutting business imperatives.

At its height, the domestic apparel sector employed over 900,000 workers. That number has dwindled to fewer than 100,000 today. The implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994 marked a turning point, opening the floodgates for U.S. companies to move production to Mexico and, subsequently, to countries throughout Asia.

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, later succeeded by the World Trade Organization, also played a critical role in liberalizing the flow of goods, making it easier for U.S. brands to access cheap labor and less-regulated production environments.

Offshoring wasn’t driven solely by regulatory or trade policy changes. Companies aggressively pursued lower operating costs, aiming to boost profit margins by leveraging global labor markets.

Manufacturing apparel in countries like China, Vietnam, and Bangladesh enabled brands to drastically reduce labor and infrastructure expenses. Technological advancements in logistics, telecommunications, and shipping also made it increasingly viable to manage far-flung supply chains efficiently.

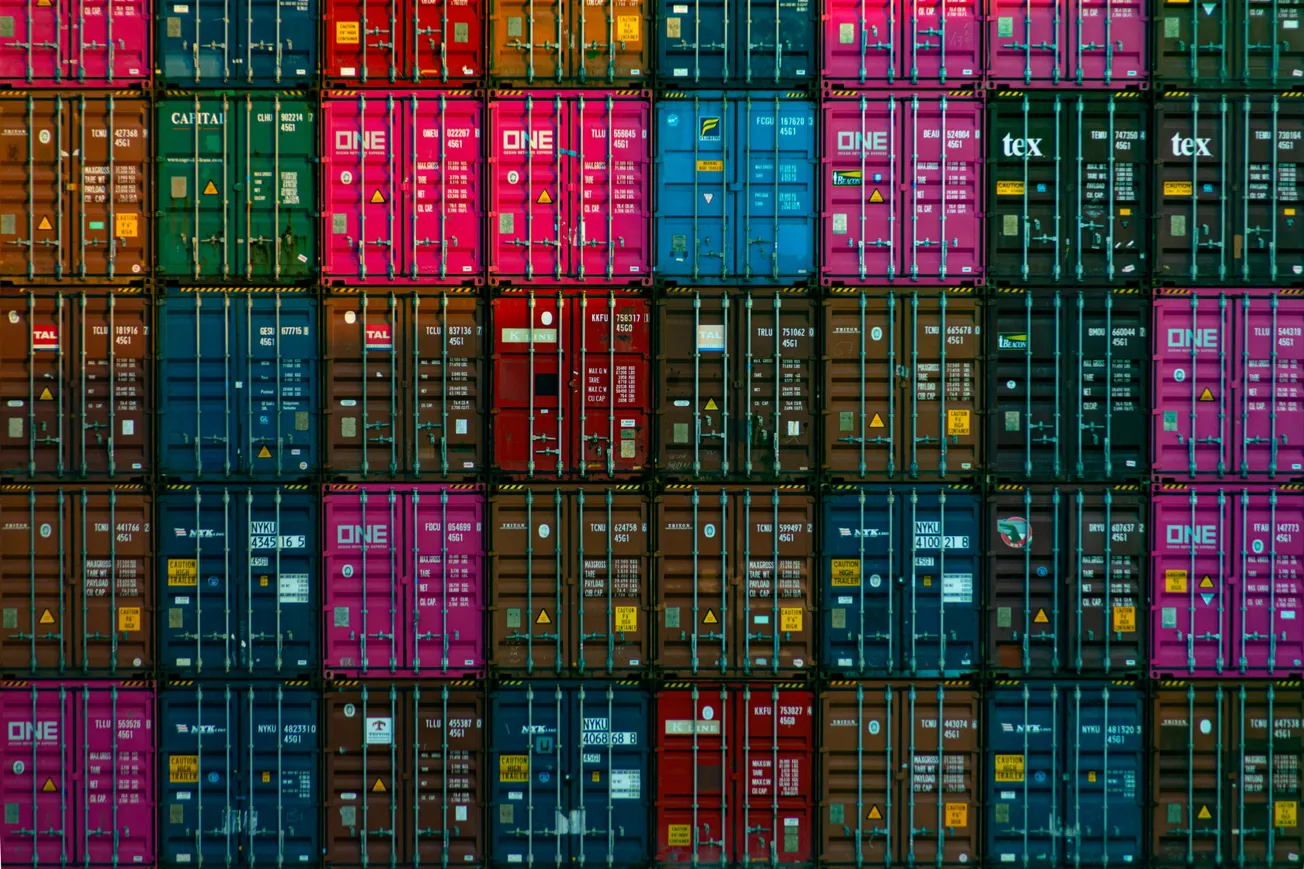

Containerization, real-time inventory tracking, and international quality assurance systems helped companies monitor production from a distance with minimal oversight cost.

These changes led to a profound decline in U.S.-based textile mills and garment factories. As manufacturers exited, communities that had once thrived on sewing floors and cutting tables faced economic dislocation. Skilled labor in the U.S. became scarce, and domestic manufacturing capacity shrank accordingly.

By the turn of the millennium, the apparel sector in the United States had been thoroughly reshaped into a design-and-distribution model, with physical production occurring largely overseas.

The Challenges Facing Reshoring Today

Efforts to bring apparel production back to American soil confront multiple, interwoven challenges.

Foremost among them is the reality of higher domestic production costs. U.S. labor laws mandate minimum wage thresholds, benefits, workplace safety standards, and overtime pay — all of which are absent or less rigorously enforced in many offshoring destinations.

The cost to produce a basic T-shirt in Los Angeles, for example, can be several times that of producing the same item in Dhaka or Ho Chi Minh City. As a result, domestic producers struggle to compete on price without significantly automating or repositioning their value propositions.

Beyond labor, infrastructure remains a significant barrier. The hollowing out of the industry over several decades has left the U.S. without the manufacturing scale or specialized regional ecosystems that still exist in Asia.

The textile mills, dye houses, button suppliers, and finishing facilities that once formed a dense network across the southeastern United States have disappeared or converted to other uses. In their place, vast and integrated manufacturing clusters have emerged in places like Guangdong and Zhejiang provinces in China, where raw materials, labor, and logistics align in ways the U.S. can no longer easily replicate.

There’s also the question of supply chain dependency. While a garment might be sewn in the United States, the fabric, threads, zippers, and buttons often still originate abroad.

These inputs can be subject to international shipping delays, tariffs, and geopolitical instability. The current tariff structure — particularly the 25% import duty reinstated on Chinese textile goods under renewed Trump-era trade policy — poses additional cost burdens on U.S. producers attempting to source affordable materials.

This creates a paradox in which reshoring efforts are still tethered to a global supply chain vulnerable to the very volatility reshoring is meant to avoid.

Regulatory complexity adds to the equation. U.S. labor and environmental laws, while providing critical protections, introduce bureaucratic hurdles that can delay or complicate new manufacturing initiatives.

Startups and small manufacturers in particular cite permitting, compliance audits, and legal overhead as substantial barriers to entry. These factors combine to make large-scale reshoring efforts both capital-intensive and fraught with red tape.

Emerging Opportunities and the Momentum Behind Reshoring

Despite these structural impediments, several trends are converging to create momentum for domestic manufacturing. Chief among them is consumer demand for ethically made, sustainable products.

Increasingly, U.S. shoppers are asking where and how their clothing is produced, driven by concerns over forced labor, environmental degradation, and supply chain transparency. A “Made in USA” label — once viewed as a niche market differentiator — is now a value proposition that resonates across broader swaths of the consumer base.

Apparel companies that manufacture domestically have found success marketing their products as higher quality, environmentally conscious, and socially responsible.

Technological advances are also changing the economic calculus. Robotics, 3D knitting machines, and AI-driven pattern cutting are reducing the labor input required for garment production. These innovations allow manufacturers to offset high labor costs and maintain competitive pricing.

Automation cannot fully replace human craftsmanship, especially in areas requiring dexterity and flexibility, but it significantly enhances productivity and enables small-batch, just-in-time manufacturing — a model increasingly preferred by e-commerce platforms and direct-to-consumer brands.

On the policy front, federal initiatives are beginning to support a manufacturing renaissance. The Fashioning Accountability and Building Real Institutional Change (FABRIC) Act, introduced in Congress, proposes a combination of tax incentives, grant funding, and wage protections to revitalize the U.S. garment industry.

By incentivizing domestic investment and penalizing wage theft, the bill aims to level the playing field for ethical U.S.-based manufacturers while promoting a high-road economic model.

Though still making its way through the legislative process, the FABRIC Act has garnered support from labor unions, sustainability advocates, and a subset of fashion brands seeking alternatives to global outsourcing.

Moreover, recent global crises — including the COVID-19 pandemic and the disruptions to shipping routes in the Red Sea — have exposed vulnerabilities in long, brittle supply chains.

Apparel companies that once relied on just-in-time inventory from Asia experienced backlogs, container shortages, and inventory write-downs. These challenges have forced a re-evaluation of risk tolerance and increased interest in nearshoring or reshoring to build more resilient production systems.

Case Studies in Domestic Apparel Production

Some companies have already demonstrated that domestic manufacturing is viable — albeit at a premium.

American Giant, a U.S.-based apparel company known for its durable hoodies and classic styles, manufactures entirely in the United States. The company has built a vertically integrated supply chain involving cotton growers in the South, spinners in North Carolina, and cut-and-sew operations in the Midwest. While their products cost more than fast fashion equivalents, the brand has cultivated a loyal customer base willing to pay for quality and traceability.

Other startups are experimenting with microfactories — small, modular production units located in urban centers — to fulfill custom or on-demand orders. This approach reduces inventory waste, lowers overhead, and provides faster turnaround times for e-commerce sellers.

Brands leveraging this model, such as Ministry of Supply in Boston or Los Angeles-based Reformation, are redefining what U.S. apparel manufacturing can look like in a digital-first economy.

However, these examples remain exceptions rather than the rule. For every American Giant, there are hundreds of brands that continue to depend on overseas production for the vast majority of their inventory. Scaling the American manufacturing base to meet even a modest percentage of current demand would require coordinated investment, labor development, and capital outlay on a scale not yet seen.

The Role of Trade Policy and Political Dynamics

The future of reshoring in the apparel industry is closely tied to the direction of U.S. trade policy. With President Donald Trump signaling a return to more aggressive trade measures, the apparel industry faces renewed uncertainty. Tariffs, while intended to protect domestic jobs, often increase costs for U.S. companies that still rely on imported inputs — a dynamic that has drawn criticism from both apparel manufacturers and retailers.

Industry leaders have voiced concern over these tariffs, noting that higher import duties can disproportionately hurt smaller brands and retailers already operating on thin margins. While tariffs may encourage domestic investment in theory, in practice they have raised prices for consumers without significantly altering sourcing behavior.

Still, the strategic imperative to reduce dependency on geopolitically volatile regions like China has given weight to arguments for a more regionally diversified manufacturing strategy — one that includes North America and, potentially, the U.S. itself.

A Cautious but Evolving Outlook

The probability of a large-scale reshoring renaissance in the apparel industry remains limited in the near term, but not impossible.

The most likely scenario involves a hybrid model in which high-margin, ethically branded, or fast-response items are manufactured domestically, while commodity basics continue to be sourced abroad. This bifurcated approach allows companies to capitalize on the benefits of both cost efficiency and brand differentiation.

The reshoring trend may gain more momentum if further supply chain shocks occur or if labor conditions abroad become untenable from a brand risk perspective. Likewise, if consumers are increasingly willing to pay a premium for “Made in USA” goods, companies may find the economics of domestic production more favorable.